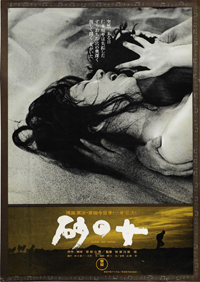

Woman in the Dunes [1964] – Hiroshi Teshigahara

Beginning with the first shot of the opening credits and never stopping for a moment, Woman in the Dunes manages to grab the viewer’s attention throughout and hold on for dear life. While being a stark, powerful visual accomplishment the film also manages to encompass personal and societal themes that continue to stay relevant. Here is an iconic piece of avant-garde cinema that is both accessible, and deserving of its many acknowledgements and accomplishments.

Forthcoming…

Black Moon [1975] – Louis Malle

“I find it very hard when I’ve made a film and people see it and ask ‘What were you trying to say?’ Of course what one’s trying to say is right inside the film. There’s nothing else to add … A film like this is something that even I don’t totally understand and that’s what I think is interesting about it … I think it’s up to each viewer to connect the film in his or her own personal way. I made the film, I put it out there… and I think my role ends there.” – Louis Malle on Black Moon

Black Moon is a perfect example of how viewing a film with a completely critical and analytical eye can sometimes lead the viewer astray. Louis Malle’s 1975 surrealist journey plays more like a stream-of-consciousness dream than a narrative, which certainly doesn’t take from it’s overall value. As Malle stated in the above quote, there’s no specific meaning of the film as a whole, thus any individual’s interpretation is as legitimate as any. Black Moon shifts more toward a dream rather than a story due to its ambiguity, vivid visuals and striking scenarios. Utilizing the cinematography of Sven Nykvist (long time collaborator and director of photography for Ingmar Bergman) each shot seems to jump out of the screen with lucid color and precise composition. Filmed at Malle’s own 200 year old manor and surrounding estate in lush southwest France, the exteriors are bleak yet beautiful, showcasing rich stretches of green grass coupled with sparse dying trees and a somber sky. The interiors feel full of life with bright, contrasting colors and endless bric-a-brac. Every shot brims with dream-like feeling and Nykvist deservedly won a French César award for his cinematography (The film also won a César for its mesmerizing sound design).

Regardless of the film’s vague imagery, certain broad themes are apparent. As the main character Lily (Cathryn Harrison) drives down a somber country road, she finds herself in the middle of a quite literal war between men and women, with the men lining up numerous military garbed women and swiftly executing them. After eluding her own death, Lily comes across a group of similarly guised women beating down a male from the opposition. This battle is representative of the second-wave feminism movement in France which was happening during the time in which Malle was shooting Black Moon. Femininity as a whole is an over-arching theme of the whole film with our main character Lily, who is discovering her own femininity throughout and going through a kind of sexual awakening. Her encounters with countless snakes throughout could be construed as coming face to face with her own sexuality, which she in the end acknowledges and accepts as a snake slithers up her skirt. By the end of the film she is largely empowered and manages to escape the raging war between the sexes that is constantly raging outside her window.

Like Alice going down the rabbit hole, Lily in Black Moon embarks on a puzzling journey that is both intriguing and enticing to the senses. Though there are imprecise themes and sweeping allegory throughout, this ambiguity strengthens the fantastic image being presented and makes it feel like a truly “new” experience. Due to Malle’s imagination and Nykvist’s precise eye (along with Criterion’s beautiful Blu-Ray transfer) it’s difficult to refute that Black Moon is a surrealist masterpiece.

Further Reading:

Black Moon: Louis in Wonderland by Ginette Vincendeau

Black Moon @ The Criterion Collection

Black Moon @ Mubi

Midnight in Paris [2011] – Woody Allen

With Woody Allen’s filmography spanning over 40 years and over 40 films, this is surprisingly only the second of his works that I’ve seen in full. The other being Annie Hall, I consider myself a fan of his work and an appreciator of his humor. After viewing Midnight in Paris, my thoughts of him are maintained due to the light-hearted, intelligent and witty nature of the film. Though devoid of an auteur-like aesthetic and major character development, Midnight in Paris succeeds in illustrating the purity and romanticism of the past while drawing a genuine appreciation for living in the moment.

Owen Wilson plays the lead of the film as Gil, a Hollywood screenwriter who wishes to replace his current craft with his long time love, literature. Though usually put off by the overwhelming acting style of Wilson, his performance here is subtle and delicate. Gil is visiting Paris with his fiancé Inez (Rachel McAdams), who is a materialistic snob to the highest degree. While dining with Inez’s far right parents (Kurt Fuller, Mimi Kennedy), they run into an old friend of Inez, Paul (Michael Sheen), who seems to be bursting with erroneous and hasty “facts” about everything he encounters. Gil immediately winces at Paul’s egotistical demeanor, and leaves the group to wander through Paris in a buzzed stupor as Inez, Paul and Paul’s wife Carol (Nina Arianda) go out dancing. Finding himself lost and sitting on a stoop, a nearby bell rings midnight and Gil is visited by an old-fashioned car diving by on the road. The passengers invite him to join them and he is transported back to the Paris of the 1920s, surrounded by his literary and artistic idols of old.

The ensemble group of artists Gil encounters are played by a similarly ensemble group of actors, with Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Gertrude Stein and Salvador Dali being played by Corey Stoll, Tom Hiddleston, Kathy Bates and Adrien Brody, respectively. Though I wasn’t familiar with some of the historical figures portrayed in the film (Cole Porter, Josephine Baker, Man Ray), their particular achievements weren’t of paramount importance. Seeing Gil’s expression of awe in the presence of his idols is truly delightful and Wilson approaches the performance with such care that his character’s wide-eyed disposition feels as authentic as can be. Gil finds his counterpart in Adriana (Marion Cotillard), a fashion designer and mistress of Pablo Picasso that is as much of a “traveler” in the era as he is. Through Gil’s new relationships he gains insight on what he’s looking for in life and how he can attain happiness. The film is less about his romantic relationships and more about how he learns from observing the past and seeing the true natures of these iconic individuals that he’d only previously known through accounting history.

Midnight in Paris is a light, intelligent romantic comedy that has no pretension and refreshing wonder. Clad with a philosophical air rather than a desperate grasp for emotion, Woody Allen has created a film that provides an easy breath of life for anyone that neglects their current situation. Neither challenging nor heavy-handed, Midnight in Paris fulfills its purpose with ease and grace.

House [1977] – Nobuhiko Obayashi

“The power of cinema isn’t in the explainable, but in the strange and inexplicable.” – Nobuhiko Obayashi

Strange and inexplicable are perfect words to describe House, in the most endearing way possible. Walking a tightrope between fantasy and horror, Nobuhiko Obayashi’s cult masterpiece embodies youthful energy and artistic ingenuity to produce a jaw-dropping work of art that fastens a firm grip on the viewers minds and transports them into a psychedelic world of childhood imagination. While just hearing some of the film’s content will invoke fascination (a girl-chomping piano, a blood-spewing feline), the visual execution is impossible to sum up in words.

The story follows seven girls donned with descriptive names a’la The Seven Dwarves (Gorgeous, Prof, Melody, Kung Fu, Mac [Stomach], Sweet and Fantasy). The group takes a visit to the house of Gorgeous’s mysterious Auntie and as soon as they arrive they’re flung into a downward spiral of madness. One after another, the girls are “eaten” by the house, in the least literal sense possible. This includes a watermelon being retrieved out of a well turning into a severed head that bites one of the girls on the ass, and a girl being attacked by futons and pillows which then turn her into a toy doll. When the script for House was completed, none of the directors at Toho wanted to undertake the project due to it being unfilmable, but Obayashi made it all work utilizing his experience directing commercials and working on experimental films.

The script itself was developed by Obayashi using ideas given to him by his eleven year old daughter because he admired the imaginations of children above adults. His unique visual style perfectly complements the story’s content, using crude matte effects and bright colors that take hold of your senses. The effects themselves were supposed to look as artificial as possible in order to make the film feel more childlike, and it succeeds perfectly. Obayashi’s experience working in commercials has a clear influence on the pacing of the film, where the cuts are sometimes so quick that it’s difficult to be sure of what’s happening. Another contributing factor to this disorientation is the soundtrack, which centers around a slow and somber piano sequence that’s coupled and interrupted with bizarre and jarring sound effects such as cat noises, babies crying and constant screams.

House is something that needs to be seen in order to be believed. Criterion’s edition includes some great supplements including Obayashi’s early experimental film Emotion and retrospective interviews with Obayashi and other crew members that worked on the film. This film is truly remarkable and deserves to be seen by everyone. What are you waiting for?

Further Reading:

House: The Housemaidens by Chuck Stephens

House @ The Criterion Collection

Red Desert [1964] – Michaelangelo Antonioni

In Red Desert, Michelangelo Antonioni utilizes color photography to show the overwhelming neuroses that can be felt in a constantly changing and progressing world. The film accents massive and powerful machinery from the onset which often are decaying, monolithic figures that infect their surroundings with flames and chemicals. Antonioni films them in such a way that they overwhelm the landscape and snuff out the natural, yet they are brimming with power and are testaments to the will and innovation of man. The director’s keen eye allows him to suggest numerous themes and emotions purely visually, and through his composition and use of color the viewer can breach the main character’s psyche and inspect her neuroses through a personal and individual perspective.

The opening scene of the film brings Giuliana (Monica Vitti) and her young son to the daunting industrial wasteland surrounding the factory her husband Ugo (Carlo Chionetti) works at. Donning a bright green coat, Giuliana stands out among the machinery and men dressed in gray as a creature of natural beauty. Her face instantaneously portrays her anxiety of being in such a place, yet those who surround her (including her son) appear to be at ease, not phased by the overbearing sights and sounds. Giuliana’s solitary human interaction at the factory is when she buys a factory worker’s half eaten sandwich off him, although she could just as easily walk to the corner and buy a new one herself. This exchange highlights her desperation for genuine human interaction while overcoming the environment that haunts her. Ironically, after buying the partially eaten food she retreats to a spot out of sight of all of the men, as well as her own son, where she can eat the sandwich alone. As she eats Antonioni once again brings the camera inside her mind as she scans the area around her and sees the toxic wasteland at her feet. Flames can be seen shooting from towers in the background just has her mind begins to gear into overdrive and her overwhelming discomfort increases. Eventually she has to give up the sandwich, as her single organic moment has been ruined by the altered landscape that surroundings her.

This scene is very telling regarding the nature of her neurosis and how it progresses and intrudes on her day to day life. The simplest of moments for Giuliana can be destroyed as she notices small man-made changes around her that get larger not only physically, but more so within her own mind. Antonioni’s soundtrack aides in showing the extent of this intrusion by having the factory sounds sometimes completely engulf the dialogue. Beyond these diegetic elements, Antonioni also inserts mystic electronic noises and tones when Giuliana’s anxiety becomes overbearing. The inclusion of these sound elements shows that although the real elements that surround her can be daunting, they become frightening when her mind distorts them to a point of complete misunderstanding. When it’s revealed that she had been in the hospital where she’d attempted suicide, the viewer is already familiar with her neuroses though it hasn’t been explained by words. Giuliana continues to try and take her temperature hoping that her sickness can be cured by doctors, but these futile attempts lead to more of the same.

The illness that overcomes Giuliana’s life is about the people that surround her as much as the environment that surroundings her. Those around her don’t understand why she feels the way she does about the world and any attempts to help her are completely arbitrary. This is particularly true of her husband Ugo, of whom Giuliana seems to have no connection to aside from sharing a son. Wrought with nightmares of being pulled into quicksand, she explains her feelings to her husband the best she can. He responds by speaking to her like a child and begins to kiss her with purely sexual intentions, seemingly without interest regarding her personal wellbeing. This kind of disinterest fuels her neuroses to new levels and introduces extreme disconnection not only from her surroundings but also from the people within them.

When Giuliana meets and begins to spend time with her husband’s friend Corrado Zeller (Richard Harris), he seems to understand how she feels about the world, at least more than her husband does. Corrado is also lost in the world, but in a much different way. He keeps moving around from place to place looking for a change, yet things always end up the same for him. Giuliana is the opposite, with constant fear of change and always wanting to be near the familiar. Corrado immediately takes great interest in Giuliana and seems to find something fascinating about her. When Giuliana’s neuroses get out of control and she has nowhere left to turn to, she goes to Corrado’s hotel room looking for solace in the one person she believes understands. To her dismay, he begins to force himself upon her in the apparent ultimate goal of his constant attention toward her. She eventually gives in, and afterward exclaims that not even he could help her, the one person she expected could. Giuliana is once again all alone, with the one person she believed had genuine interest in helping her having been sexually motivated the whole time.

Following this final attempt for solace, Giuliana brings herself to a dock where she walks past numerous massive and decaying ships. Looking up at the deathly monuments she is once again completely overcome with the man-made earthly changes as a result of commerce. Stammering and confused, she confronts a sailor and begins to speak in fragments, unable to form a cohesive sentence. After dismissing the idea of becoming a passenger on the boat, she has a moment of realization. Speaking to the stranger, she says “Everything that happens to me is my life,” in an understanding that she must accept things for the way they are because she has no control over changing them. Though she is undoubtedly still a victim within her own mind, this acceptance is a large step toward improvement and it gives hope for Giuliana to eventually accept the way things are and to no longer become a victim within her own psyche.

Though Red Desert is full of imagery of humans polluting the earth and filling it with dirty, decaying structures, its main function is not to abhor human’s effect on the environment. There are moments when the work of man is seen as truly terrifying and harmful, yet there are others in which man’s work is marveled for its scale and ingenuity. This is particularly true in the scene when Giuliana is talking to the man working on the radio tower for the University of Bologna, in which she displays genuine interest in the work that’s being done there. Even though she is overcome with fear regarding man’s changes in the world, she can’t help but marvel in some of the achievements. Even someone like Giuliana, who comes near destruction due to her outlook toward change, can see the beauty in some aspects of human production. This realization is a hopeful one and strives for people to accept change and see the beauty in all of man’s work. The film isn’t a negative outlook toward life and man’s work, but a particularly interesting and artistic look toward the effect a rapidly changing world can have on a person. With Michelangelo Antonioni’s striking imagery of both beauty and decay, viewing Red Desert is a personal struggle between the two and the victor is decided by the individual viewer alone.

leave a comment